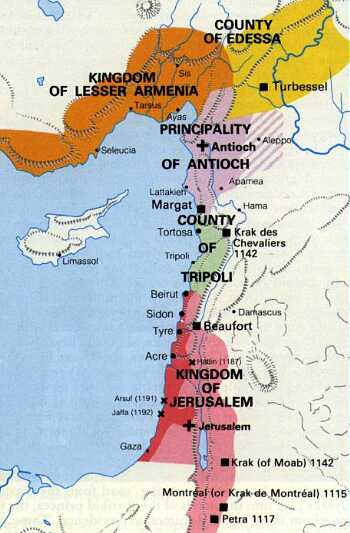

The crusador states

Antioch was to provide the major trauma of the entire Crusade. The great leaders - Godfrey, Bohemond (Europe/Hauteville), Raymond, the two Roberts, Stephen of Blois (Europe/Champagne), Hugh of Vermandois and Bishop Adhémar - agreed that the capture of the city was vital. If left alone, its Turkish garrison would harass the Christians in their winter quarters, and be poised to take them in the rear should Muslim armies arrive from the east. To the ordinary pilgrims, however, Antioch was simply one of the three holiest cities of Christendom, along with Jerusalem and Rome, and it was unthinkable to leave it in infidel hands. St Peter's original see had been Antioch and had preached here in a cave used as a temporary chapel. He had coined a new name for those who believed in the teachings of Christ, previously called 'Nazarenes', had been described for he first time as 'Christians'. St Luke was a native of Antioch and it was here he had written the Acts of the Apostles. As a result of its long association with the foundation and spread of Christianity the place had more than its fair share of Christian churches and monasteries, the most important of which the Turks had blasphemously converted into mosques. So in some ways the capture and liberation of Antioch was a dress rehearsal for the relief of Jerusalem itself.

|

Every effort was put in hand for its capture. By late October 1098 the main army was approaching the city, which lies a few miles inland from the northeastern corner of the Mediterranean. The Christians needed every soldier and every horse that could be mustered, so the roving captains - Tancred and the others - were called in to swell the ranks of the main army. Only Baldwin, far away in Edessa, was allowed to stand aside. No one doubted that the Turks would defend Antioch fiercely.

The Host camped a mile from the city walls and took stock of their situation. Even from that distance the city's defences were awesome. Antioch's perimeter wall was said to contain 360 towers, nearly one for every day in the year, and within its circumference enough room to pasture the warhorses of a small army. Immediately behind the city rose Mount Silpius, a rocky peak which was incorporated into the defences and crowned with a citadel that was claimed with some justification to be impossible to storm. Even the sight of the stiff climb to the summit was enough to take one's breath away. From the mountain-top citadel the boundary wall followed the ridge eastward, and was carried across a narrow gorge to the neighbouring peak. From there it dropped spectacularly down the mountainside almost to the bank of the river Orontes and turned to run parallel to the river, at times built right on the bank so the Orontes would serve as a natural moat. This massive wall was made of huge stones held together with an unknown and unbreakable mortar and it continued until it completed the circle by climbing the slope of the mountain back up to the citadel.

But the leaders themselves still retained enough confidence after their victories against the Turks to reject the notion of any delay. They wanted to finish the affair before the Muslims counterattacked from Aleppo or Damascus, so the war council ordered siege positions to be taken up without delay. The Christians were puzzled that 'the blare of horns, the neighing of horses, and the crash of arms intermingled with the shouts of men', produced no reaction whatsoever from the Turkish garrison. 'An utter silence prevailed in the city. Not a sound or noise of any kind was heard from it.' Antioch might as well have been empty of defenders.

Yaghi Siyan, the Turkish governor, was watching to see how the besiegers would spread themselves. It was physically impossible for the Christians to surround the city, even ignoring the lofty Mount Silpius side which was too rugged to blockade. Instead the Franks decided they had enough manpower to invest just three gates and the northeast quadrant of the wall. Bohemond, who for his own reasons was the most enthusiastic to prosecute the siege, took up the key position facing the Gate of St Paul from which issued the Aleppo Road. To his right were the Northern French contingents led by Robert of Normandy and the Count of Vermandois, together with Robert of Flanders and Stephen of Blois - who watched over the Gate of the Dog. Next to them came the Provencals of Raymond of Toulouse and Bishop Adhemar. Finally, clustered around the gate which would later be called the 'Gate of the Duke' in his honour, were the 'Lotharingians, Frisians, Swabians, Saxons, Franks and Bavarians' of Duke Godfrey. Two other gates, the Gate of St George which faced west and the main river gate, the Gate of the Bridge, where a stone bridge crossed the Orontes, were left largely unattended.

In panic the Christians ran back to the bridge of boats, hoping to cross to the comparative safety of their camp. But the pontoons were too narrow to carry the stampeding throng, and many men were pushed or jostled into the water and were drowned. By this time the knights in camp had been alerted and organized a counterattack. Hurrying to the stone bridge, they managed to intercept the Turks returning with the booty seized from the Christian foragers. As the Turks were fighting their way steadily towards the city gate, they were reinforced by the townsfolk who unbarred the gate and poured out to their help. The knights were surprised by the ferocity of the attack and were themselves driven back towards the bridge of boats. Once again there was a great deal of tumult and shoving, so that some of the knights also, while fleeing from the pursuing foe, became so jammed together on the bridge, that they were thrown headlong into the river. Burdened with shields, breastplates, and helmets, they were swallowed up with their horses by the waters and never again appeared.

The other point of danger was the Gate of the Dog, built over a marshy patch where a small stream issued from under the city wall. The defenders had a habit of suddenly throwing open this gate, rushing across the bridge that spanned the marsh, and loosing off an arrow storm at Count Raymond's troops who were camped nearby. These impromptu attacks caused so many casualties among the Provencals that the first idea was to destroy the bridge. A call went out for mallets and iron implements, and equipped with these tools a demolition party of mailed knights went on to the bridge and attempted to prise it apart. But 'the solid masonry, harder than any iron, offered effective resistance. The citizens [of Antioch] also hindered their attempts by hurling forth stone missiles and showers of arrows.' The knights' next scheme was to close the bridge with a stout wooden tower that would be constantly garrisoned by men-at-arms. This mini-fort was constructed with great labour and hauled forward under the usual rain of rocks and darts from the city walls. But once again the Christians had underestimated the verve and dash of the defenders. The Turks launched a brisk counterattack, surged right up to the mobile tower, and set it alight, burning it to ashes. Foiled yet again, the Provencals drew off and came up with their third plan. This time they stationed three 'engines', stone- or dart-throwing machines, in such a way as to sweep the bridge and keep up a bombardment on the city gate itself. For a while the plan worked, and as long as the machines kept up their fire, no citizen dared sortie from Antioch. But as soon as the fire slackened, when the operators lost interest or ran out of projectiles, the sorties began allover again. In exasperation Count Raymond's troops finally decided that there was nothing for it but to eliminate the gate entirely. Under covering fire from the 'machines,' the armoured knights assisted by ordinary footsoldiers rolled up huge rocks and tree trunks and piled such a mass of them against the gate that it was no longer usable.

But this was no more than self-protection. The Christians were meant to be on the attack but were behaving more and more as if they were on the defensive, and soon the inevitable shortage of food heightened this back-to-front version of a siege. Hunger began to afflict, not the Turks safe inside Antioch with their prepared stocks of provisions, but the profligate Franks outside the city walls. When the nearby countryside had been swept clean and the foraging parties had to go farther and farther afield to find increasingly meagre spoils, they were exposed to ambushes set by Turkish guerrillas. Resentment grew against the local Christians of the region, Syrians and Armenians, who profited from the army's distress by selling their produce at vastly inflated prices. Unable to find enough money, some of the poorer pilgrims died of starvation.

The army's pavilions and tents were rotting, and gave little protection from the heavy rain showers and penetrating cold. Some of the Europeans had fondly imagined that a Mediterranean winter would be mild and sunny in those regions, but by mid-December they were rudely disabused. 'Winter here is exactly the same as our winter in the West', wrote Stephen of Blois glumly to his wife. Pilgrims and soldiers had scarcely anywhere dry to sleep or keep their baggage. Their clothes, as well as the precious food, went mouldy. The camps became muddy quagmires. A pestilence broke out, and men and women, already weakened by famine and cold, died in such great numbers that 'there was scarcely room to bury the dead, nor could funeral rites be performed'.

Day by day conditions in the camp worsened. Life became dominated by a frantic search for food. 'The famished,' wrote Fulcher of Chartres, 'ate the shoots of beanseeds growing in the fields and many kinds of herbs unseasoned with salt, also thistles which, being not well cooked because of the lack of firewood, pricked their tongues.' The most desperate ate the skins of dogs and rats, and even picked out the undigested grains from animal droppings. As famine gnawed deeper and pestilence spread, a sense of hysteria took over. The appalling conditions were identified as God's punishment for the sins of the pilgrims. An earthquake, followed by a blood red sunset, were interpreted as signs of God's wrath. The pilgrims believed that they had forfeited His grace by their immorality. So if the Host was to be saved, it must make amends for its ungodly ways. By common consent a strict regime of penitence was devised. The camp prostitutes were expelled, and 'adultery and fornication of every description was forbidden under penalty of death, and an interdict was placed on all revelling and intoxication.' The ban extended to all dangerous games of chance, heedless oaths, fraud in weights and measures, chicanery of every kind, theft and rapine.' The measures were formally approved by Bishop Adhemar in his capacity as the Pope's legate, and special judges were appointed to enforce them with full powers of investigation and punishment. The one act of atonement which no one would have found difficult to observe was the call for a three-day fast so 'that, by scourging the body, they might strengthen their souls for more effective prayer.' As there was hardly any food to be had, this not only made a virtue from necessity, but was a novel way of rationing. Without a trace of irony, William of Tyre recounted that the effect of the fasting and abstinence of the army was that Lord Godfrey who was, as it were, the one and only prop of the whole army, at once began to recover fully from the serious illness which had long troubled him, the result of a wound which he suffered from a bear in the vicinity of Antioch-in-Pisidia. His convalescence was a source of the greatest consolation to the entire army in their affliction.

This despairing reversion to their original high-minded ideals is one of the most striking developments in the story of the First Crusade. Since the original departure from their homes, there had been comparatively little evidence of extreme religious fervour as the host trudged across Europe to Constantinople, then on into Anatolia. Even the ordeals of the mountains and the crossing of the deserts had been borne without any undue calls for heavenly assistance. But now, unnerved by the steadily deteriorating conditions at Antioch, the travellers turned back to their religion for salvation and comfort. Significantly, their reformation took place at a time when several of their leaders were devising ways to reap more worldly rewards from the Crusade.

The siege of Antioch was the darkest hour of the Crusade and also its most glorious memory. It was described by every major chronicler, and their reports became the grist for all manner of ballads and stories. The suffering and eventual victory at Antioch were to be legendary. Those who came out of the ordeal well, were to join the pantheon of heroes. Those who failed or deserted were to be execrated for ever. It was here that Duke Godfrey's reputation as the peerless leader and perfect knight took hold.

Bohemond was cast by the storytellers as the warrior chief, crafty and ruthless. Bohemond's genius as a field commander was crucial. He had been complaining that he was running out of money and would have to withdraw from the expedition, and to appease him the other leaders gave him more authority on the battlefield, with immediate results. The Muslim ruler of Aleppo, Ridwan, assembled a relief force and in early February had sent it to within fourteen miles of Antioch before it was detected. Every active knight in the Christian camp was mustered, and they rode out to meet the enemy, leaving the infantry to guard the camp. Each major leader led his own column of knights into the engagement but Bohemond was allotted the strategic reserve and decided the outcome of battle. Just as the Christian line began to buckle, Bohemond ordered his standard bearer to charge into the thick of the fighting. According to the Gesta knight: That man, fortified on all sides with the sign of the Cross, went into the lines of the Turks, just as a lion, famished for three or four days, goes forth from his cave raging and thirsting for the blood of beasts. So violently did he press upon them that the tips of his renowned standard flew over the heads of the Turks. Moreover, as the other lines saw that the standard of Bohemond was gloriously borne before them, they went back to the battle again, and with one accord our men attacked the Turks who, all amazed, took to flight.

The Turks set fire to their own camp to prevent it falling into enemy hands so the loot was meagre, but the victorious knights did return to camp with some food and, equally important, a large number of remounts. To advertise their success to the disappointed garrison of Antioch, the heads of 200 Turks were impaled on stakes to face the city walls.

An Egyptian envoy who had been visiting the Christian camp now wished to return down the ambush-infested road to the port at St Simeon. The plan was that the escorting troops led by Bohemond and Raymond would then bring back additional supplies and escort new pilgrims who had arrived by sea to join the Host. Word reached camp that the supply column had been ambushed. Everywhere was consternation and doubt. No one knew whether any of the column had survived and whether both Bohemond and Count Raymond were lost. Duke Godfrey, fully restored to health, promptly instructed the herald to sound the general alarm. The entire army had to report for duty - any shirkers were threatened with death - and was divided into columns under the Duke of Normandy, the Count of Flanders, and Hugh of Vermandois. Duke Godfrey had just delivered the usual encouraging speech to the troops when Bohemond and Raymond both straggled in, to be greeted with immense relief. They approved of Godfrey's plan, which was essentially to repay the Turks in kind by setting an ambush for them along their return road to the city.

They were almost too late. The returning Turks showed up before the army was fully in position, and a furious hand-to-hand combat took place right under the city walls as the Turks tried to get back across the stone bridge. A gallery of spectators, the women and wives of Antioch, looked down from the walls. In this tournament atmosphere all the barons naturally performed splendid deeds of valour as far as the chroniclers were concerned and there was a great slaughter of the enemy all around the approaches to the bridge. But Duke Godfrey excelled. As the exhausted enemy were jostling to get back in through the gate which Yaghi Siyan had opened, the Duke performed a deed which was to become renowned in story and ballad. Toward evening in the struggle around the bridge, he gave a notable proof of the strength for which he was so distinguished. . . . With his usual prowess he had already decapitated many a mailed knight at a single stroke. Finally, he boldly pursued another knight, and though the latter was protected by a breastplate, clove him through the middle. The upper part of the body above the waist fell to the ground, while the lower part was carried along into the city astride his galloping horse.

'This strange sight,' said William, recognising the birth of a legend, 'struck fear and amazement to all who witnessed it. The marvellous feat could not remain unknown, but rumour spread the story everywhere.' William was writing within the lifetime of men who had fought at the battle of Antioch, and even if the tremendous swordstroke was entirely imaginary, Duke Godfrey's reputation as the doughty warrior of Christ was assured.

That night and during the following day while the Christians celebrated their victory, burial parties crept out from Antioch to gather up the corpses of the Turkish dead and inter them in the Muslim cemetery opposite the Gate of the Bridge. It was wasted effort. The Christians decided to build a watch tower, long overdue, facing the Gate of the Bridge, and the masons pillaged the Muslim cemetery for materials, using the gravestones in the construction. The fresh graves were robbed by the soldiers, looking for jewels, weapons and gold buried with the slain, unashamed to loot infidel graves. The tide was at last beginning to turn in favour of the Franks. On payment of one hundred marks in silver, Tancred was commissioned to build a third watchtower opposite St George's Gate and make sure that no one went in or out. Now the only gate available to the garrison was a small postern which led out through a narrow defile between Mount Silpius and the adjacent peak. Though the Christians had, more or less, blockaded the city and cowed the garrison, they were no nearer to capturing Antioch. There had not been a single direct assault since the day they had taken up their positions. There had been no attempt to mine the walls or break in the gates. The defences of Antioch, among the most up-to-date in the Levant, had not been scratched.

It was left to Bohemond, once again, to devise the masterplan. Perhaps remembering the Byzantine success at suborning the garrison of Nicaea, Bohemond made contact with a disaffected captain of one of the city watchtowers, Firuz. He seems to have been a renegade Armenian Christian who had converted to Islam, but was prepared to betray his section of the wall in exchange for money and a gift of land. First, however, Bohemond called a meeting of the army council and suggested that whoever managed to arrange the capture of Antioch would be given the city. The other leaders were outraged. All had laboured for the city's fall, they said, all should share in its capture. But reports then reached them that a large Muslim army under the command of Kerbogha, Atabeg of Mosul, and was marching to the relief of Antioch. After wasting three weeks unsuccessfully besieging Baldwin in Edessa, Kerbogha's army had regrouped, picked up reinforcement from Aleppo and Damascus and was now closing in on Antioch. If the Christians failed to capture Antioch in the next few days, they would be caught between Kerbogha and the Turkish garrison and crushed. Faced with imminent and total disaster, the other leaders with the exception of Raymond were forced to agree to Bohemond's suggestion - always provided Emperor Alexius did not come to their aid - and he revealed his plan to take the city by treachery.

So came the most glamorous and daring episode of the campaign. The entire Christian army made a great show of marching out of camp as if to go off to meet Kerbogha but after setting off along the Aleppo road, it doubled back after nightfall and in the early hours of the morning was in new positions close under the city wall. Bohemond and a hand-picked band of sixty knights, including the Gesta knight, who reported on the whole adventure, crept their way to the base of the section of the wall commanded by Firuz. He had charge of a key post known as the Tower of the Two Sisters, and since Antioch's perimeter was so long, it was impossible for Yaghi Siyan to supervise all his sector captains all of the time. Bohemond's knights placed a single ladder against the wall, and most of the raiding party scrambled up, among them Bohemond himself and, according to some of the more colourful accounts, Duke Godfrey and the Count of Flanders. In the darkness and hurry the ladder was overloaded and broke. For one appalling moment the raiders were nonplussed. They were penned up on the parapet, and unable to descend into the city. Luckily someone found a small gate on their left which they broke open and were able to go down into Antioch. Raising a great clamour they charged down to the main gates, killing anyone in their path, and opened the city to the rest of the army.

The exulting Christians poured in and spread throughout the street, running into the buildings and putting Muslims to the sword. Some of the garrison managed to flee up the mountain and into the citadel on Mount Silpius where they bolted the gate and were safe. Another band of Turks trying to ride out over the steep crags by the northern canyon, were so hotly pursued that they were driven over the cliffs to their deaths. 'Our joy over the fallen enemy was great,' reported Raymond d' Aguilers in a grisly assessment, 'but we grieved over the more than thirty horses who had their necks broken there.' Yaghi Siyan himself managed to get out of the city on horseback, but was recognised by some Armenians when he stopped at a farm house. They killed him, cut off his head and brought it to the camp for reward.

Antioch had fallen on 3 June 1098 and just in time. Three days later the advance units of Kerbogha's relief force appeared only to find that the Christians had disappeared into the undamaged city. The besiegers had become the besieged.