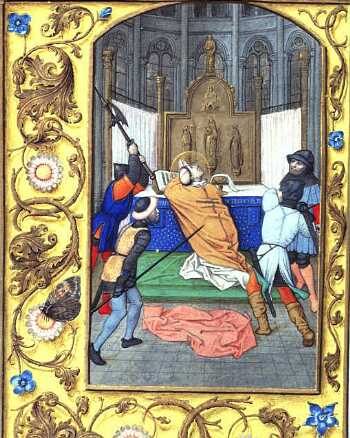

The martyrdom of Thomas Becket

Thomas Becket, the son of a wealthy Norman merchant living in London, was born in 1118. After being educated in England, France and Italy, he joined the staff of Theobald, the Archbishop of Canterbury.

|

When Henry II became king in 1154, he asked Archbishop Theobald for advice on choosing his government ministers. On the suggestion of Theobald, Henry appointed Thomas Becket as his chancellor. Becket's job was an important one as it involved the distribution of royal charters, writs and letters. The king and Becket soon became close friends. Becket carried out many tasks for Henry II including leading the English army into battle.

When Theobald died in 1162, Henry chose Becket as his next Archbishop of Canterbury. The decision angered many leading churchmen. They pointed out that Becket had never been a priest, had a reputation as a cruel military commander and was very materialistic (Becket loved expensive food, wine and clothes). They also feared that as Becket was a close friend of Henry II, he would not be an independent leader of the church.

After being appointed Thomas Becket began to show a concern for the poor. Every morning thirteen poor people were brought to his home. After washing their feet Becket served them a meal. He also gave each one of them four silver pennies. Instead of wearing expensive clothes, Becket now wore a simple monastic habit. As a penance he slept on a cold stone floor, wore a tight-fitting hairshirt that was infested with fleas and was scourged daily by his monks.

Thomas Becket soon came into conflict with Roger of Clare. Becket argued that some of the manors in Kent should come under the control of the Archbishop of Canterbury. Roger disagreed and refused to give up this land. Becket sent a messenger to see Roger with a letter asking for a meeting. Roger responded by forcing the messenger to eat the letter.

In 1163, after a long spell in France, Henry arrived back in England. Henry was told that, while he had been away, there had been a dramatic increase in serious crime. The king's officials claimed that over a hundred murderers had escaped their proper punishment because they had claimed their right to be tried in church courts.

Those that had sought the privilege of a trial in a Church court were not exclusively clergymen. Any man who had been trained by the church could choose to be tried by a church court. Even clerks who had been taught to read and write by the Church but had not gone on to become priests had a right to a Church court trial. This was to an offender's advantage, as church courts could not impose punishments that involved violence such as execution or mutilation. There were several examples of clergy found guilty of murder or robbery who only received "spiritual" punishments, such as suspension from office or banishment from the altar.

The king decided that clergymen found guilty of serious crimes should be handed over to his courts. At first, the Archbishop agreed with Henry on this issue but after talking to other church leaders Becket changed his mind. Henry was furious when Becket began to assert that the church should retain control of punishing its own clergy. The king believed that Becket had betrayed him and was determined to obtain revenge.

In 1164, the Archbishop of Canterbury was involved in a dispute over land. Henry ordered Becket to appear before his courts. When Becket refused, the king confiscated his property. Henry also claimed that Becket had stolen £300 from government funds when he had been Chancellor. Becket denied the charge but, so that the matter could be settled quickly, he offered to repay the money. Henry refused to accept Becket's offer and insisted that the Archbishop should stand trial. When Henry mentioned other charges, including treason, Becket decided to run away to France

Under the protection of Henry's old enemy. King Louis VII, Becket organised a propaganda campaign against Henry. As Becket was supported by the pope, Henry feared that he would be excommunicated. Becket eventually agreed to return to England. However, as soon as he arrived on English soil, he excommunicated the Archbishop of York and other leading churchmen who had supported Henry while he was away. Henry, who was in Normandy at the time, was furious when he heard the news and supposedly shouted out: "Will no one rid me of this turbulent priest?"

Four of Henry's knights, Hugh de Morville, William de Tracy, Reginald Fitz Urse, and Richard de Bret, who heard Henry's angry outburst decided to travel to England to see Becket. Becket had already received a letter warning him of danger when, on the afternoon of 29 December, the four knights came to see him at his episcopal palace. The account that follows is drawn from a number of different sources.

During their interview with Becket, the knights made several demands - in particular, that he give absolution to the bishops whom he had excommunicated. He refused. The knights withdrew, 'uttering threats and oaths'. A few minutes later, Becket heard people shouting, doors banging open and a clashing of arms. Urged on by his attendants, he began moving slowly through the cloisters to the cathedral. It was now twilight and vespers were being sung. At the door to the north transept, he was met by some terrified monks, whom he commanded to get back to the choir. They withdrew a little and he entered the church. When the knights were spotted behind him, the monks slammed the door and bolted it. In their confusion, they also shut out several other monks, who began beating loudly on the door.

Becket turned and cried, 'Away, you cowards! A church is not a castle!' He reopened the door himself, then went towards the choir. All but one of the monks - Edward Grim - fled to the crypt and other hiding places. The knights broke through the door, shouting, 'Where is Thomas the traitor?'

'Here I am,' he replied, 'no traitor, but archbishop and priest of God!' The knights shouted at him to absolve the bishops. Becket answered firmly: 'I cannot do other than I have done.' He turned to one of the knights. 'Reginald, you have received many favours from me. Why do you come into my church armed?' Fitzurse made a threatening gesture with his axe. 'I am ready to die,' said Becket, 'but God's curse on you if you harm my people.' There was some scuffling as they tried to force the archbishop outside. Fitzurse flung down his axe and drew his sword. 'You pander! You owe me fealty and submission!' exclaimed the archbishop.

Fitzurse shouted back, 'I owe no fealty contrary to the king!' and knocked off Becket's cap. At this, the latter covered his face and cried out to God and the saints. De Tracy struck a blow. It first hit the arm of Edward Grim, who was nearby holding the archbishop's crozier, then grazed Becket's skull. He wiped away the blood running into his eyes and cried: 'Into Thy hands, O Lord, I commend my spirit!' Another blow from de Tracy beat him to his knees, and he pitched forward on to his face, murmuring, 'For the name of Jesus and in defence of the Church, I am willing to die.' With a vigorous thrust, Le Bret struck deep into his head, breaking his sword against the pavement, and Hugh de Morville added a blow, although the archbishop was now dying.

The murderers, brandishing their swords, now dashed through the cloisters, shouting: 'The king's men! The king's men!' The cathedral filled with people, initially unaware of the catastrophe, and a thunderstorm broke overhead. Becket's body lay in the middle of the transept, and for a time no one dared to approach it.

When the news of Becket's murder was brought to the king, he shut himself away and fasted for 40 days, for he knew that his chance remark had sent the knights to England bent on vengeance. Pope Alexander excommunicated the four knights and prohibited Henry from taking mass until he made reparation for his sins. This he did on 21 May 1172. At a ceremony of public penance at Avranches in Normandy, he swore, among other things, not to obstruct any appeals to Rome by the clergy and to abolish all customs prejudicial to the Church.

The Christian world was shocked by Becket's murder. The pope canonised Becket and he became a symbol of Christian resistance to the power of the monarchy. His shrine at Canterbury became the most important place in the country for pilgrims to visit. In 1172 Pope Alexander III and absolved Henry from Becket's murder. In return. Henry had to provide 200 men for a crusade to the Holy Land and had to agree to being whipped by eighty monks. Most importantly of all. Henry agreed to drop his plans to have criminal clerics tried in his courts.

In February 1173, the pope promulgated a bull of canonisation, declaring Thomas Becket a saint only a little more than two years after his martyrdom. The following year, on 12 July, Henry fasted, donned sackcloth and ashes, walked barefoot through Canterbury to the cathedral while being scourged by 80 monks and spent the night at Becket's elaborately and expensively decorated tomb.