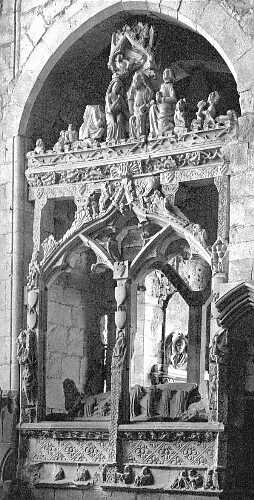

Lord John was buried in the magnificent tomb that has now come to rest under a makeshift arch

in Cartmel church. His effigy was cut by a sculptor on a solid block of sandstone nearly seven feet

long.

Robert and Christiana's son Thomas, and their grandson Michael, must have continued to live at Harrington because they were described in the Register of St Bee's as 'de Haverington', as their fathers had been. Osulf's property of Flemingby had perhaps been whittled away in grants to the Church: at least, that is what appears from the action of Michael's son Robert in 1277. He laid a claim to the manor of Flemingby against the Abbot of Holm Culton.

Robert was claiming lands that had belonged to his great-great-grandfather Osulf. So the Plea Roll of 1277 contains a pedigree of his descent, confirming the evidence of the Register of St Bee's. Robert was compelled to yield all of the manor to the Abbot, except three hundred and eighty acres.

|

But if Robert was disappointed by this result, he was amply compensated by the death of his wife's brother. His wife Agnes was the daughter of Sir Richard Cansfield, on whose death the rich manor of Aldingham passed to Agnes's brother William. But William was drowned in the River Severn, and through this sad event Robert and Agnes were translated to the moated manor of Aldingham, on the shores of Morecambe Bay in Lancashire

Only a square moat below Mote Hill remains today as the probable site of the original manor house. The inquisition of 1347 described it as possessing a garden and a dove-house, two hundred and forty acres of demesne land, one-third fallow, a third meadow and a third pasture. It was a pleasant seat to which Sir Robert and Agnes removed, beside the encroaching sea. But today no trace remains of their family's residence there except a stained-glass window, containing the Harington device of the silver fret, in the ancient church. The fret, as it has been worn by the Haringtons ever since, is an interlace identical to the pattern carved on bone Viking combs at Jarlshof in Shetland.

The son of Sir Robert and Lady Agnes Harington was called John. He was born in 1281, a hundred years after his ancestor Osulf of Flemingby stepped out of the night of legend. John, first Lord Harington of Aldingham, is the founder of his family's greatness, and the progenitor of everyone of his name who appears in this record of its fortunes.

When John was only twelve years old his mother Agnes died, and four years later his father died also; Sir William Dacre became his guardian during the five remaining years of John's minority. He would have been wise to marry John to his daughter Joan. But there is no historical evidence that he did so. On John's tomb in Cartmel Priory church the escallops of Dacre alternate with the Harington fret, but the heraldic evidence is not conclusive.

On 22 May 1306 John Harington of Aldingham attended a ceremony in London, whose splendour he could not have seen equaled in the north. He was ceremonially knighted in the Palace of Westminster in the company of Edward Prince of Wales, after which he accompanied the elder Edward, hammer of the Scots, across the northern border.

Edward I died in the following year, and was succeeded by a son who had little taste or aptitude for war. John was summoned for military service from 1309 to 1335, so he may have been present at the field of Bannockburn. He took part with the Earl of Lancaster in the treasons, which culminated in the murder of the King's favourite Piers Gaveston, and received the wretched King's pardon. He was cautious in his adherence to Lancaster. When he was forbidden to attend the Earl's meeting of 'good peers' at Doncaster in 1321 he stood aside, and so escaped Lancaster's fate after the rising of the following spring. When he was outlawed for treason in the Scottish marches two years later, he once again secured a royal pardon. John Harington kept himself just, and only just, within the bounds of safety during those unruly times.

He was summoned as a man of weight and judgment to the Council of Magnates at Winchester in 1324 and to Parliament, as a Baron, from 1326 until his death in 1347. So the peerage of Harington was founded by writ of summons. Up in the north, John led the busy administrative life of the fourteenth-century magnate. He was the custodian of a truce with the Scots. He was appointed to various commissions of the north to decide causes, and to array the local forces. At Aldingham he improved his estate, and obtained a king's license to enclose three hundred acres of land, wood, moor, and marsh to make the park upon which the inquisition commented at his death.

|

When he died, he was buried in the magnificent tomb that has now come to rest under a makeshift arch in Cartmel church. His effigy was cut by a sculptor on a solid block of sandstone nearly seven feet long. The surcoat bears the fretty device of his house that must have identified him in the Scots wars. The interlaced chain mail is minutely carved, and its folds at the elbows and other loose places are defined with masterly skill.

Lord John left a lively family tradition which his descendants were to follow to their great gain and their greater loss. The form which this tradition was to take is outlined in the bare facts of Lord John's own career. He had inherited wealth, and therefore power, through the provident marriage of his father. He had supported the house of Lancaster to the point of treason. Above all he, the first of his name ever to have been summoned as a baron to Parliament, had shown no more respect for an anointed king than for any of his subjects. It was this irreverent attitude to kingship which was to distinguish his descendants above all else, and ultimately to cause their ruin.

Sir John Harington of Farleton lived quietly in that still untroubled valley. He married Katherine, the daughter of Sir Adam Banastre, executed by Edward II, and he held his patrimony, by the service of a rose yearly, of his nephew the second Lord John, and he died in 1359. The first Lord John's heir Robert had died before his father, in Ireland. But he had lived long enough to receive his knighthood and to marry a great heiress, Elizabeth Moulton of Egremont Castle in Cumberland.

When Sir John's second son Nicholas was already master of Farleton when he was sixteen years old. Nicholas inherited this property unexpectedly when his elder brother died abroad. It seems that he had already had time to develop the ambitions of the younger son who must seek his own fortune, and their horizon was suddenly enlarged when first his father, then, two years later, his elder brother died. It seems almost certain that Sir Nicholas lived at the manor of Farleton in the Lune valley as his father had done. But not a trace of a medieval manor house remains there.

In 1362, the year of Sir Nicholas's succession to Farleton, there occurred an event of the utmost significance to the Haringtons, to Lancashire, and to the throne of England. John of Gaunt was created Duke of Lancaster by virtue of his marriage with the late Duke's daughter. 'Our very dear and well beloved' Nicholas Harington, 'our Sheriff of Lancaster': so John of Gaunt would address Sir Nicholas in the many letters enrolled among the Duchy records. The first evidence of his advance to a position of such trust and power occurs in 1367, when Sir Nicholas came of age.

|

Sir Nicholas took care to support the foreign war that John of Gaunt continued in the wake of the Black Prince, without becoming closely involved in it himself. In December 1368 he was a member of the commission that raised a hundred archers in Lancashire for the army with which Gaunt landed at Calais. Then, in 1372, he went to Parliament as one of the two knights of the shire representing the county of Lancaster. He had taken the first step that was to lead to the complete domination of the representation of Lancashire by his descendants.

The career of Sir Nicholas Harington is one of the most fascinating success stories in the fashion of the Middle Ages. His co-operation in foreign wa:rs was judicious, his representation in Parliament indefatigable at a time when others sought to be excused. In his matrimonial alliances he was unerring. He married first a daughter of Sir Thomas Lathom, and secondly Isabella, daughter of Sir William English. By Isabella he begat his two remarkable sons, and by either or both of his wives he obtained the lands in Cumberland, Yorkshire, Westmorland, and South Lancashire of which he was found to be the owner in 1400. The marriages he arranged for his children were more spectacular still.

How powerful he had become by the time he was twenty-seven years old appears in an incident that occurred the year after he first entered Parliament. On 1 March 1373 a Dacre laid complaint that Sir Nicholas had come to Beaumond in Cumberland with a following of three hundred armed men, and had there destroyed houses, assaulted servants and tenants, and driven away horses, cattle, and sheep worth £50. Whatever the cause of this turbulence may have been, it is not without significance that a Dacre complained in vain.

In 1375 Sir Nicholas was a member of two commissions appointed by the King to apprehend murderers. In 1377 he again returned to Parliament at the accession of Richard II: and there he will have witnessed the ceremony when his more placid cousin Robert, third Lord Harington, was knighted at the King's coronation

So Sir Nicholas reached the highest offices of Lancaster, and helped to cement the power that was to deprive King Richard of his throne. The year after the coronation, being thirty-two years old, he first held the office of Sheriff of Lancaster for a year. Then he returned to Westminster for the Parliament of April 1379, and by the summer he was sheriff again, petitioning for the customary allowance for parchment and ink. In days when men must combine such responsibilities with such feats of physical endurance as all those journeys on horseback involved, it is no wonder that young men were preferred.

In 1384 Sir Nicholas had been appointed by Gaunt to a commission which brought him again into contact, in novel circumstances, with his cousin Robert of Gleaston. A Genoese ship had been wrecked on the coast near Furness Abbey on the detached segment of Lancashire, the other side of Morecambe Bay. The cargo had been plundered by the men of Furness, and the commission was authorized to restore all their merchandise to its Genoese owners. The chief culprits were the Abbot of Furness and Robert, Lord Harington of Gleaston. Perhaps the strong arm of Sir Nicholas was weakened by the claims of kinship, for no restitution had been made four years later.

|

Sir Robert Neville of Hornby possessed an only son, whose only daughter John of Gaunt married to his own son, the Duke of Exeter. Hornby was to be the inheritance of a king's grandson. Nevertheless Sir Nicholas saw fit to marry his elder son and heir, William, to Sir Robert Neville's daughter Margaret. The chances that the Haringtons would ever succeed to Hornby Castle must then have appeared slight, and they were only slightly improved by the death of Sir Robert Neville's son in 1387, without leaving any other heirs than the Duchess of Exeter.

Meanwhile Sir Nicholas continued to serve the Duke of Lancaster in the administration of his Duchy, and the deposition of Richard II by Gaunt's son left him undisturbed. It was the rebellion of Owen Glendower and Harry Hotspur that gave him his most decisive opportunity to serve Henry IV as he had served his father. On 7 August 1402 a royal mandate commissioned Sir Nicholas with eight others, including the sheriff and steward of the county, 'to supervise and try all the fencible men of the county'. This force was to meet the King at Shrewsbury and march with him into Wales against Glendower. The same September Sir Nicholas rode to the Parliament at Westminster for the last time. He was now fifty-six years old but he was to end his days as energetically as he had ever lived them.

The following spring King Henry moved north to do battle with the Percies at Shrewsbury. And six days after their defeat on July 21 an order was sent to eight great men of Lancaster, including Sir Nicholas, to assemble all the knights, esquires, and yeomen of the county to meet the King at Pontefract and do battle with Percy, Earl of Northumberland, as he advanced to the aid of his son. Sir Nicholas witnessed the Earl's submission: then he died, leaving his son William heir to Farleton.

So the first nine generations of the Haringtons live still in the remaining records of those two hundred years of English history. Their features and their thoughts are indistinct: only the personalities of the first Lord John and of Sir Nicholas of Farleton emerge with any clarity. The ruins of their castles and their scattered memorials in churches do not help to bring the others back to life. But collectively they were invoked by their descendants constantly in times of prosperity, and particularly when misfortune befell the inheritors of their proud name. That is their most conspicuous memorial, the conscious family tradition which they bequeathed to their posterity.

After the battle of Bosworth the Haringtons of Exton became the senior representatives of their family. While their cousins in the north were pursuing such eager and adventurous lives, these Haringtons were content to follow the quiet pastoral ways. Their origins were identical to those of the Farleton branch, only they began a generation later. John, first Lord Harington, had given to his younger son the manor of Farleton that he inherited from his Cansfield mother. Lord John's eldest son was married to the heiress of Moulton, and her younger son was likewise given a manor out of her inheritance.

|

It was Fleet in Lincolnshire, and because Fleet contained three manors, Robert Harington's became known as Fleet Harington. His son John married into one of the neighbouring manors, taking to wife the daughter of Laurence Fleet of Fleet. So the process of settlement and accumulation began. John's son Robert married Beatrice, the heiress of John de la Laund. The marriage settlement, executed in 1405, is the oldest family document remaining in the hands of their descendants today. It represents a triumph compared with the marriage of the preceding generation, but compared with the next it was a bagatelle.

The manor of Exton in Rutland descended, and still descends, with the blood royal of Scotland. At the moment when Osulf entered the pages of English history, it was owned by the brother of William King of Scots. With the crown of Scotland it passed to the family of Bruce, and so to Sir Nicholas Greene, the husband of Jane Bruce. His tomb is the oldest in Exton church. It was his great-grand-daughter Katherine Colepeper, heiress of Exton, who married the heir of Robert and Beatrice Harington.

His name was John Harington. He lived to see the death of his cousin John, fourth Lord Harington, and the extinction of the barony in the male line. He saw his cousin Sir John grow up, heir to Hornby Castle, and saw him perish with his father at Wakefield. Compared with these, John Harington of Exton had been brought up in modest circumstances. Well may he have reflected on the vicissitudes of life when he found himself heir to the Bruces and senior representative of his house.

The little village of Exton still lives today undisturbed in its ancient tranquillity. It lies about five miles from the market town of Oakham amidst fields of arable and pasture, and considerable woodland. The village green is caqopied with trees, and from it run lanes of houses built in warm weathered stone, almost all of them thatched. The church in which Sir Nicholas Greene was buried stands apart from the village, in the park of Exton Hall. Here John and Katherine Harington brought up Robert their heir.

In 1492, while his cousins were tasting the ruin that has blotted their very fates from the records of history, this Robert Harington of Exton became High Sheriff of Rutland. He was sixth in descent from the first baron, buried in Cartmel church, and he was first of the six generations of Haringtons to hold the office of Sheriff of Rutland in unbroken succession. Robert became Sheriff of Rutland again in 1498, and he died in 1501. It was left to his son John to make the next advance.

|

First, Sir John obtained a knighthood. This may not have appeared to him a matter of great consequence, because he could not have known what part he was playing in preserving the title in the senior representative of his house for what is now over six hundred years. Secondly, Sir John became High Sheriff four times, but in this his father had set the precedent. He set one of his own when, in 1517, he purchased the neighbouring manor of Horn. Another manor adjoining Exton was settled on his daughter Alice, at her marriage, by her father-in-law. But the significance of the Horn transaction is that it was the first of the series of purchases with which the Haringtons supplemented their marriage settlements, to build up one of the largest landed fortunes in England.

Finally, Sir John Harington of Exton was buried at his death in 1524 in Exton church, and his monument there is the earliest after that of Sir Nicholas Greene. Shafts of light from the unstained window by the south door gleam on the white alabaster effigies of John and his wife, he in plate armour, she in hood and full length gown. John's head rests on a mantled helmet surmounted by the collared lion's head of the Harington crest, and his feet are supported by a dog, marvellously carved. There are sixteenth-century tombs of greater magnificence, but not of more arresting art.

Source: "The Harington Family" by Ian Grimble